Reinforcing the Importance of PV and ADR Management

What are the odds of getting killed by a cough syrup? For most of us, this sounds impossible. Yet, this has become today’s reality. More than 20 children in India have died not from a deadly disease, but from a spoonful of cough syrup given for the flu. Imagine your own five-year-old child catching a simple flu, and like any concerned parent, you administer a syrup that is commonly prescribed and trusted in every household. Little would you know that you are poisoning your toddler with a single spoon.

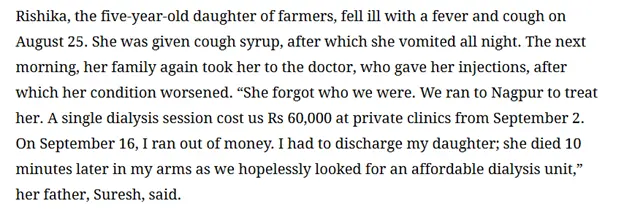

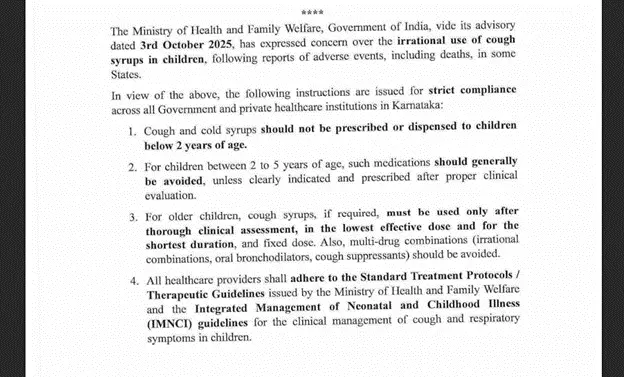

This is exactly what happened to Suresh, a farmer who spent ₹60,000 at a private hospital trying to save his five-year-old daughter, Rishika. She vomited through the night, her condition worsening with each hour. At the hospital, she was given injections and kept under observation, but her condition only deteriorated. “She forgot who we were. We ran to Nagpur to treat her. A single dialysis session cost us ₹60,000 at private clinics from September 2. On September 16, I ran out of money. I had to discharge my daughter; she died 10 minutes later in my arms as we hopelessly looked for an affordable dialysis unit,” Suresh recalled. His words paint a heartbreaking picture of helplessness.

How many more fathers like Suresh must lose their children before authorities wake up and prioritize pharmacovigilance in India? Why, in an age where AI is transforming industries, does pharmacovigilance still struggle to function without obstacles?

As highlighted by Springer, “There was a time when investing in national PV systems was considered a luxury by underdeveloped and developing countries, as access to medicines was generally limited and the safety monitoring of products that were not available to most of their populace was considered unimportant. But global initiatives by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other organizations subsequently improved access to medicines on a large scale in many low and middle-income countries which in chorus triggered the demand for PV systems to ensure patient safety, given the pharmacological rationale for the need for PV in every country.”

In India, pharmacovigilance has had a fragmented journey. Initial attempts in 1986, 1989, and 1997 to establish a system failed. The National Pharmacovigilance Programme (NPP) launched in 2004 showed some progress but no significant impact. This eventually led to its re-conceptualization and relaunch as the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI) in 2010. Today, pharmacovigilance is regulated by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), which oversees PvPI to ensure the safe use of medicines. Yet, the challenges remain daunting: underreporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), lack of trained professionals, limited awareness in rural areas, and poor quality and consistency of data.

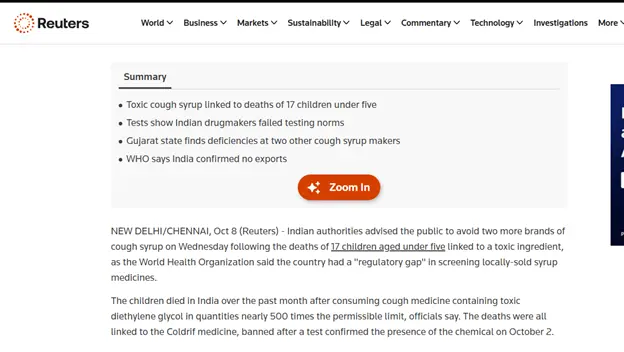

The recent tragedy was caused by contamination with diethylene glycol (DEG) a toxic solvent and humectant used in industrial processes such as polyester resins, plasticizers, antifreeze, gas processing, and textile finishing. While it has a wide range of industrial applications, DEG is highly poisonous. History has seen multiple mass poisonings where it was incorrectly substituted for pharmaceutical ingredients. Its danger lies in its deceptive nature: a colorless, syrupy liquid easily mistaken for safe excipients like glycerine when proper quality checks are skipped. In this case, poor oversight and cost-cutting enabled a deadly error.

This loss could have been prevented if pharmacovigilance systems had worked with diligence and accountability. Rishika could still be alive, playing in her garden or coloring walls with crayons. Instead, her parents live with an irreplaceable void. It shows how negligence in one corner of the pharmaceutical chain can cause damage that no compensation, no words, and no promise can ever undo.

Ironically, India is celebrated worldwide as the “Pharmacy of the World.” Its pharmaceutical industry is recognized for its vital role in producing vaccines, essential medicines, and generics that sustain global healthcare, especially during COVID-19. As the Prime Minister has said, “It is because of the efforts of the pharma industry that today India is identified as ‘pharmacy of the world’.” This recognition is not new; India’s knowledge of medicine is rooted in ancient history. The Ayurveda and Siddha systems meticulously documented the sourcing, compounding, and dispensing of natural medicines. Dhanvantari, considered the lord of healing, and Sushruta, the father of surgery, laid foundations that the world still acknowledges. From the ancient period, India’s legacy has been selfless service to humanity through medicine.

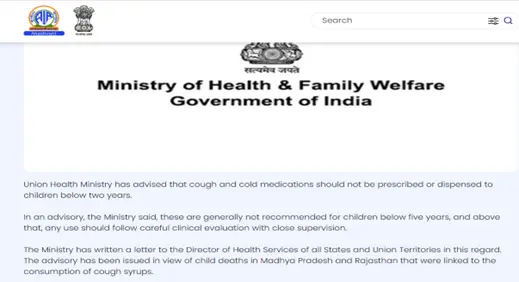

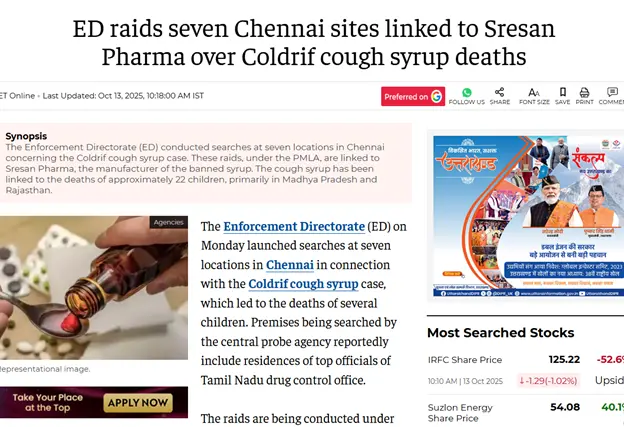

That is why today’s failures are so condemnable. They tarnish centuries of credibility and threaten the reputation India has built on both ancient wisdom and modern innovation. The state of Madhya Pradesh acted swiftly by banning Coldrif syrup and other medicines from Sresan Pharmaceuticals, with Chief Minister Mohan Yadav announcing ₹4 lakh compensation to the families of the deceased and committing to cover hospitalization costs. At the national level, CDSCO launched risk-based inspections of drug manufacturing units across Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. These inspections focus on cough syrups, antipyretics, and antibiotics critical steps to prevent another disaster.

Recent Developments and Global Response

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a global alert urging countries to strengthen regulatory oversight and quality assurance in pharmaceutical production, particularly for oral liquid formulations vulnerable to contamination with diethylene glycol (DEG) and ethylene glycol (EG). “This is an issue which has been going on for 90 years or more,” says Naseem Hudroge, an analyst at the World Health Organization’s team on substandard and falsified medical products. In alignment with this call, the Government of India and the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) have undertaken a series of decisive actions. The government has made DEG and EG testing mandatory for all raw materials and finished products, embedding these tests within the Indian Pharmacopoeia to ensure enforceability. Nationwide, risk-based inspections have been initiated across six key pharmaceutical states that is Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra to identify systemic lapses and enforce compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). At the state level, Tamil Nadu’s drug regulatory authority has issued show-cause notices to Sresan Pharma, the manufacturer of the tainted cough syrup Coldrif, and has begun scrutinizing its manufacturing license. Meanwhile, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) conducted raids at seven locations in Chennai linked to Sresan Pharma, investigating possible financial irregularities and supply chain violations associated with the contaminated product. In parallel, Madhya Pradesh continues to enforce the ban on Coldrif and other toxic syrups, while the CDSCO has directed all pharmaceutical companies to procure excipients only from qualified and audited vendors with full traceability. Collectively, these measures represent a critical effort to restore accountability and transparency within India’s pharmaceutical ecosystem. Yet, the ultimate test lies not merely in new regulations but in their consistent implementation, backed by robust pharmacovigilance and uncompromising ethical responsibility to safeguard public health.

But real reform requires much more. Pharmacovigilance in India must be strengthened with:

- Advancements in Technology

Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data can automate adverse event detection, signal identification, and data management, making PV faster, more efficient, and more accurate. - Regulatory Changes

Regulatory agencies must evolve constantly, with stricter enforcement, better inspections, and clear accountability to ensure compliance and drug safety. - Globalization of Drug Development

As drug development grows more global, Indian PV professionals must align with international standards, opening opportunities for expertise in global pharmacovigilance. - Personalized Medicine

Targeted therapies and genetic treatments demand a new PV framework capable of monitoring highly specific patient outcomes and complex adverse effects. - Drug Safety in Real-World Evidence (RWE)

RWE can complement traditional clinical trial data. PV professionals must harness it to assess benefit-risk profiles in real-world use. - Interdisciplinary Skills

Pharmacology, epidemiology, biostatistics, and data science must converge in PV, enabling experts to handle complex safety datasets effectively. - Focus on Patient-Centricity

Patient voices must be heard. Engaging patients in reporting and feedback is essential to ensure their safety concerns are addressed directly.

The future of pharmacovigilance holds immense promise, with opportunities for innovation and global leadership. But it demands systemic change, continuous training, public awareness campaigns, and stronger investment in rural healthcare infrastructure to encourage ADR reporting and protect every citizen. The pharmacy of the world must first protect its own. Until that happens, tragedies like Rishika’s will continue to remind us of the cost of negligence measured not in money, but in innocent lives lost too soon.

Citations

2. Rishika’s reference: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/in-madhya-pradesh-town-with-11-cough-syrup-deaths-a-refrain-no-facility-had-to-go-to-nagpur-10289875/

3. Diethylene Glycol (DGE) https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/explained-what-is-diethylene-glycol-found-in-coldrif-cough-syrup-at-tamil-nadu-unit-9394916

4. India the World’s Pharmacy: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressNoteDetails.aspx?NoteId=152038&ModuleId=3

5. Dhanvantri and Ancient roots ; https://jntuaotpri.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/THE-EVOLUTION-OF-PHARMACY.pdf

6. Sushruta: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5512402/#:~:text=Sushruta%20is%20the%20father%20of,state%20of%20body%20and%20mind.

Sushruta is the father of surgery. If the history of science is traced back to its origin, it probably starts from an unmarked era of ancient time. Although the science of medicine and surgery has advanced by leaps and bounds today, many techniques practiced today have still been derived from the practices of the ancient Indian scholars.

7. Regulatory response: https://www.ocacademy.in/blogs/contaminated-cough-syrup-deaths-doctor-arrested/

8. The future of Pharmacovigilance: https://www.cliniindia.com/future-of-pharmacovigilance-in-india/#:~:text=What%20are%20the%20key%20challenges,of%20data%20across%20the%20country.

UPDATED CITATIONS - 13.10.2025

- Number of children’s death : https://www.npr.org/sections/goats-and-soda/2025/10/10/g-s1-92542/contaminated-cough-syrup-children-dying-criminal

2. Measures taken by Goverment: https://hfwcom.karnataka.gov.in/uploads/GO_Advisory%20regarding%20Rational%20Use%20of%20Cough%20Syrups%20in%20Children_1759846249.pdf

WHO calls out gap in India’s cough syrup testing after deaths https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/india-flags-testing-lapses-pharma-firms-after-cough-syrups-deaths-2025-10-08/

I visited multiple web pages however the audio feature for audio songs existing at this web site is genuinely wonderful.

I will immediately grasp your rss feed as I can’t in finding your e-mail subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please allow me know in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.